[ad_1]

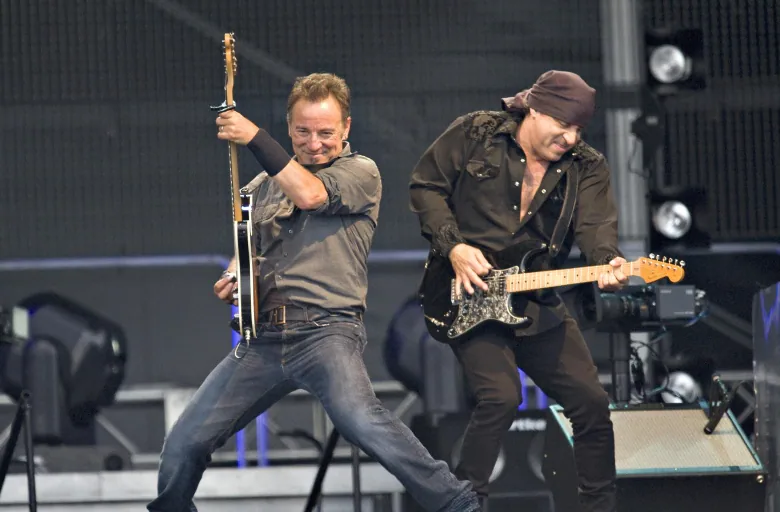

While that question stretches nearly as far back as the establishment of the ticket seller, it recently centred around around blue-collar hero Bruce Springsteen. Two weeks ago, after spending hours waiting in a digital line to get tickets for his upcoming North American tour, many fans of the Boss came face to face with all that was left: “dynamic price” tickets — which shift up and down based on demand — going for as much as $5,000 US, with all of the more modestly priced face-value tickets long gone.

And Springsteen fans are far from alone there. Back in 2018, Taylor Swift fans complained when tickets swung as high as $1,500 US, with many fans complaining they weren’t even allowed into the program that would have let them buy more modestly priced tickets in the presale.

Looking to earlier this year, Harry Styles’s regularly priced $200 tickets shot up to over $1,000 at his tour’s only Canadian stop — prompting some fans to start a petition pleading for cheaper options. Meanwhile, just last month, tickets to Drake’s OVO Fest sold out almost instantly, with “lawn” seating at Toronto’s Budweiser Stage — far from where the rapper would be performing — listed at $900.

But despite the recent examples, it’s the Springsteen debacle that reignited a decades-old battle between Ticketmaster and concert-goers. Upset over its market dominance and lack of transparency, those fans are demanding to know the reasoning behind the ticket giant’s seemingly nonsensical prices.

Given a closer look, that confusion is nothing new — it’s just a symptom of a monopolistic industry and the complicated nature of ticket-selling.

Concert-going has become more expensive

Back in 1994, alt-rock group Pearl Jam was one of the first to go toe to toe with the ticketing platform. After trying — and failing — to enforce a maximum $1.80 US service fee with Ticketmaster on their $18 tickets, the band complained to the U.S. Justice Department, saying the company broke antitrust laws, used its monopoly to charge exorbitant fees and later pushed event organizers into refusing artists access to other venues.

“It is well known in our industry that some portion of the service charges Ticketmaster collects on its sale of tickets is distributed back to the promoters and the venues,” Pearl Jam guitarist and lyricist Stone Gossard said before a congressional subcommittee in 1994. “It is this incestuous relationship, and the lack of any national competition for Ticketmaster, that has created the situation we’re dealing with today.”

Yet after a year-long investigation, the Justice Department abruptly dropped the case, with U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno citing “new enterprises” entering the ticketing industry. For his part, Pearl Jam singer Eddie Vedder had a more pessimistic reaction, telling fans at a subsequent show he “hate[d] to think it’s the wave of the future — corporate giants that can’t be toppled.”

And since then, the world of ticket sales has only become more complicated — and expensive.

For starters, there have been increasing service charges and fees added to the price of tickets, while Ticketmaster has frequently lobbied against transparency laws that would require them to explain these extra costs to buyers.

But at the same time, how we see — and value — live music has also changed.

In a 2011 interview, ex-Ticketmaster CEO Fred Rosen explained that as the internet became a central part of people’s lives, the amount and speed at which brokers could sell tickets exploded. That, combined with a number of industry changes that forced artists to rely on live music far more than record sales, transformed concerts into the expensive industry they are today.

“It used to be you made the record, and toured to support the record,” said Rosen, who left the company in 1998. “Now… you tour to make money, because pricing caught up with value and the albums don’t sell on the same level.”

Forced to focus more attention on touring — which meant dealing more with Ticketmaster — brought more problems for artists. That problem grew so much that back in 2009, Bruce Springsteen himself was forced to come out against the company.

At the time, fans complained that when trying to buy tickets at face value on the Ticketmaster site, they were redirected to a subsidiary Ticketmaster site with tickets listed by resellers at hundreds of dollars more than their original price.

Before the U.S. Federal Trade Commission investigated and reached a settlement with Ticketmaster over the claims, Springsteen’s team released a statement to apologize to fans and condemn the company.

“The abuse of our fans and our trust by Ticketmaster has made us as furious as it has made many of you,” Springsteen and his manager Jon Landau wrote on the rocker’s website, before offering some prophetic advice.

“The one thing that would make the current ticket situation even worse for the fan than it is now would be Ticketmaster and [artist manager and venue operator] Live Nation coming up with a single system, thereby returning us to a near monopoly situation in music ticketing.”

Antitrust violations

Less than a year later, the merger between Ticketmaster and Live Nation was approved by both the DOJ and Canada’s Competition Bureau.

Since then, there’s been a deluge of stories of music fans complaining — and suing — over antitrust violations, hidden fees and rising ticket prices.

As recently as 2019, Canada’s Competition Bureau ordered Ticketmaster to pay a penalty of $4.5 million for misleading customers on online ticket sales, all while the bureau also ruled the company’s practice of recruiting scalpers to secretly purchase and resell Ticketmaster tickets for inflated costs was legal.

But shortly after, the DOJ stated that Ticketmaster and Live Nation had “repeatedly and over the course of several years” violated the legal agreement that allowed them to merge, using “threatening behaviour and retaliation” to bully venues into sticking with Ticketmaster, “lest they risk losing Live Nation concerts, hindering effective competition for primary ticketing services.”

The two later reached an agreement that both extended the terms of the merger, which were set to expire in 2020, and toughened its rules. In response, the nonprofit American Antitrust Institute published a letter arguing that stronger amendments were needed, to address the fact that the harmful results of their merger on the entertainment industry “cannot be understated.”

David Bowie’s estate just sold his entire music catalogue for $250 million US — the latest in a long string of similar moves by the likes of Bruce Springsteen, Stevie Nicks and Neil Young.

Complaints continue to resurface to this day. Earlier this year, Ticketmaster and Live Nation were hit with another lawsuit, alleging they have created a “barrier to entry” for other ticketing companies, allowing them to arbitrarily inflate the prices of event tickets on both the primary and secondary (reselling) market.

Ticketmaster did not respond to a request for comment from CBC, and both Ticketmaster and Springsteen’s team have defended the dynamic pricing model. Ticketmaster told Variety that those tickets only represented about 11 per cent of what was available, while Springsteen manager Jon Landau said in a statement to the New York Times they chose prices that “are lower than some [performers] and on par with others.”

In fact, the astronomical prices that have again brought attention to the issue could be something of a red herring.

Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing model is not a new invention, said John Bergmayer, the legal director of U.S. nonprofit Public Knowledge. Also known as surge pricing, the model is meant to adapt prices to demand in real time — a complicated task that is perhaps more familiar in industries like air travel, ridesharing and hotels.

Ticketmaster labels their dynamically priced tickets as “platinum seating.” Though the name suggests a prime location, these seats can in fact be located anywhere in a venue. For certain shows, the company will simply reserve a number of tickets to have a price that can fluctuate higher or lower based on demand.

Effectively, Bergmayer explained, this means Ticketmaster acts as a reseller of its own tickets — leaving a certain number available, for much higher prices, even when a show is in high demand.

Many musicians in Canada have struggled to make a living during the pandemic because of closed venues and streaming services that average only half a cent per stream.

Ticketmaster’s website describes the practice as giving “fans fair and safe access to the best tickets, while enabling artists and other people involved in staging live events to price tickets closer to their true market value.”

Rather than an attempt to solely charge huge prices for big shows, Bergmayer said Ticketmaster promotes the technique as being primarily meant to defend against scalpers, as selling tickets for too little would result in independent scalpers selling them instead — with none of the profit going to the artists.

As to its efficacy, Bergmayer says he has his doubts.

“Ticketmaster would say that the only way [to fight scalpers] is using their system,” he said. “But there are competing systems. They don’t always work because of Ticketmaster restrictions, and they tend to be cheaper for consumers to use. But it shows that at least in terms of that metric, competition can bring prices down.”

Lack of competition harms audiences, artists

And rising costs are only becoming more urgent for consumers. According to a recent report from trade publication Pollstar, average prices for concert tickets have increased nearly 20 per cent between 2019 and 2022. But Pascal Courty, a professor of economics at the University of Victoria, said that while Ticketmaster’s monopoly is a huge issue, rising prices aren’t necessarily the worst outcome.

Without competition, Courty said, Ticketmaster can refuse to share how many tickets are sold at what price or how many are available — allowing them to create artificial scarcity. As well, he said many of the fees on top of the ticket price aren’t shown until after you select the tickets, and are not explained.

“In the end, they’re trying to create this buying frenzy for events and take advantage of it. And the lack of transparency harms the public, wastes everybody’s time and sometimes harms artists as well,” Courty said.

As for whether Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing thwarts scalpers, Courty says that’s the million-dollar question.

Ticketmaster’s current strategy is a mixture of dynamic pricing, auctions and a “verified fan” program that attempts to limit access to resellers — a strategy that proved fairly ineffective with the band Paramore just days after Springsteen’s tickets were released. In both cases, standard-priced tickets disappeared almost immediately, with only “platinum” seats remaining.

“The issue is, do you want to sell at market price? Or do you want to leave money on the table?” Courty said.

Courty believes breaking up Ticketmaster’s monopoly would help create incentive to solve these problems. But Shiraz Mawani, an independent ticket broker and YouTuber in Toronto, says it’s not that simple.

Mawani said that while the company could mitigate fan anger by making it so “verified fans” don’t somehow find themselves on a web page offering dynamic pricing after hours of waiting, the issue will persist regardless of whether Ticketmaster shrinks or grows.

“You’re always going to have this problem,” Mawani said. “There’s always going to be that discrepancy between how much someone is willing to pay at face value versus what someone’s actually gonna be paying, down the street, for market value.”

[ad_2]

التعليقات